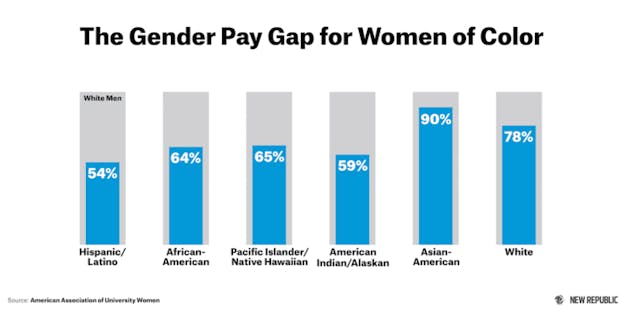

Women, on average, earn 22 percent less than men, or 78 cents for every white man’s dollar. This fact is everywhere, especially on Tuesday, Equal Pay Day. The day itself is meant to symbolize this figure, as it takes women three-and-half extra months of work to earn what men make year-round.

Critics love to quibble that a few factors easily explain this gap. They say women work fewer hours, and have less experience than male counterparts because they leave the workforce to raise children, and seek jobs and careers that may have flexible hours but pay worse. Per a “fact check” from the Washington Post’s Glenn Kessler in early April: “Unless women stop getting married and having children, and start abandoning careers in childhood education for naval architecture, a large gap in wages will almost certainly persist.” While blaming politicians for trotting out this statistic without “proper context,” Kessler somehow fails to mention his own context. The lack in the United States of policies that guarantee paid parental leave and childcare helps explain why some women have no choice but to exit the workforce or curtail their career options. The option, in realistic terms, is that women wouldn’t have children, yet critics seem fine with penalizing women economically for being caretakers and continuing the existence of the human race.

There is a problem with the 78 percent statistic, but not the one critics say. That figure obscures the fact that most women of color fare worse than white and Asian women. It is a national average, across all races, from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Compared to what a white man makes: Hispanic women earn 54 percent, followed by black women at 64 percent, and Native American at 65 percent. (The wage gap closes somewhat for women of color vs. men of the same race or ethnicity).

Women of color are more likely to hold hourly wage jobs and to work in lower-paid fields. They also tend to work fewer hours. Not because they choose it, per se, but because of the nature of the work. Black and Hispanic women are concentrated in service industries, where part-time shift work is often the only option. In 2014, 29 percent of African-American women and 28 percent of Hispanic women had no choice but to work part-time, because they were unable to find full-time work, compared to 16 percent of white women.Differences in education also don’t explain the full gap, because “many women of color tend to be paid less than their white peers even when they have the same educational background,” writes the American Association of University Women (AAUW).

Women also make the so-called choices they do, working fewer hours and staying in lower-paid jobs, because the United States lacks paid sick days and maternity leave. Additional policies helping caretakers would help women, too, but the U.S. has hardly considered, like universal pre-kindergarten education. This is so shy of what most of the developed world provides women. A year of infant childcare costs even more than in-state college tuition in most states. And, as Kessler never notes, the lack of paid leave has an invisible toll, too, because many women simply can’t leave their job for another if they are afraid of losing benefits.

Finally, there’s discrimination. Yes, it still exists. Women in the same jobs and at the same educational level as men still earn less money. Emily Baxter, a research associate at the Center for American Progress, points out, “male surgeons earn 37.76 percent more per week than their female counterparts […] And this does not apply only to high-paying, male-dominated careers: Women are 94.6 percent of all secretaries and administrative assistants, yet they earn 84.5 percent of what their male counterparts earn per week—a weekly difference of $126.” A 2012 AAUW report that controlled for workers’ relevant earning factors other than gender—education, hours worked, experience level—and still couldn’t account for 7 percent of the gap just one year out of college. That adds up to a lot of unearned income over a lifetime, especially since it grows to 12 percent after 10 years in the workforce.

The critics are right that unequal pay is nuanced. They just don’t realize that the nuances bolster the case for doing something about it.

This piece has been updated.